Over the past couple of years I’ve kept a file of different hop studies I’ve come across through various podcasts, presentations, and articles. I thought it would be beneficial (to me as least) to layout all of the different studies and pull out the highlights in an attempt to create a detailed look at different methods and concepts for achieving maximum hop flavor and aroma in beers. I’m not a scientist, I’m merely doing my best to evaluate each study and pull from them what I believe would be the most beneficial to homebrewers. If I’m misinterpreting any of the results, please feel free to let me know so I can adjust the article, I don’t want to mislead anybody! Now, let’s get into into it…

Hop Oils

Typically, discussions around hop oils tend to center around the following: Total oil amount, B-Pinene, Myrcene, Linalool, Caryophyllene, Farnesene, Humulene, and Geraniol. As an example, for the hop oils calculator I created last year, these are the oils being used in an attempt to estimate flavor and aroma descriptors of beers because these are the exact oils that Hopunion tested from the 2014 hop crop. The main hydrocarbons of hop oils are the terpenoids (like myrcene, humulene, caryophyllene etc.) which have been determined to be one of the main contributors to the hop aroma in beer. It makes sense then that most of the studies in this post center around these terpenoids. However, back in 2008 it was determined that there has been 485 hop compounds currently identified and evidence to suggest there are upwards of 1,000 hop oil compounds that may be present!1 So there is clearly way more research needed to even further understand the complexities of hop oils!

This post of common oil aroma and taste descriptors of hop oils and acids is a good quick reference guide for many of the hop oils mentioned throughout this post.

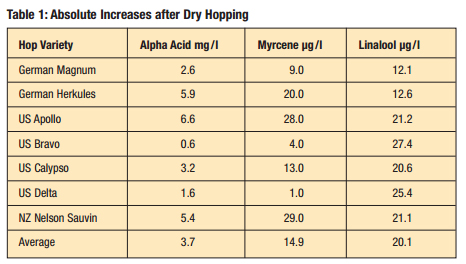

Hop Oil Behavior Throughout the Wort Boiling Process

The Kishimoto study mentioned above did some great research examining how hop oil behavior is altered during the wort boiling process. As the following graphic shows, Kishimoto found that the majority of hop oils escape during the boil. This would help explain why there has been a major move towards late hop additions in an attempt to get the more of these oils into the fermenter. The research shows that myrcene and linalool levels fell rapidly during boiling because of their low boiling points. Humulene, farnesene, caryophyllene and geraniol have slightly higher boiling points and had more of their oils remain during the boil. The study also found that among the identified hop-derived ordorants, the most intense odor-active components included linalool and geraniol. These two particular oils were also the main focus of many of the other studies in the post.

The research shows that to retain higher concentrations of these terpenoids, we should be adding hops later in the boil right? Well, this tells part of the story because the fermentation process also plays a big role!

Hop Oil Behavior During Fermentation

I have reluctantly participated in the huge whirlpool/steep additions when brewing hoppy beer. This has been the new process undertaken by most homebrewers in an attempt to get a hop saturated flavor from beers and not just the hop aroma that comes with dry hopping. I have gone along with this process reluctantly because no matter how many hops I pack into the whirlpool when it comes time to taste the post fermented beer before dry hopping, I never really get much in the flavor or aroma that suggested this wort was once jam packed with hop material. So, where did it all go?

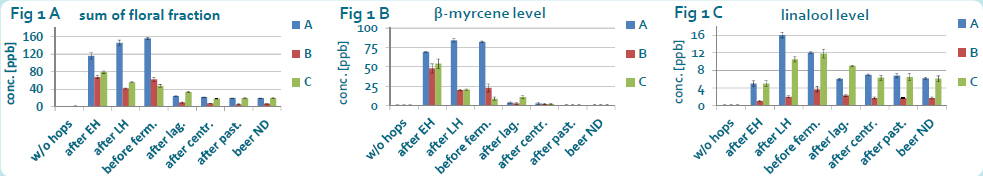

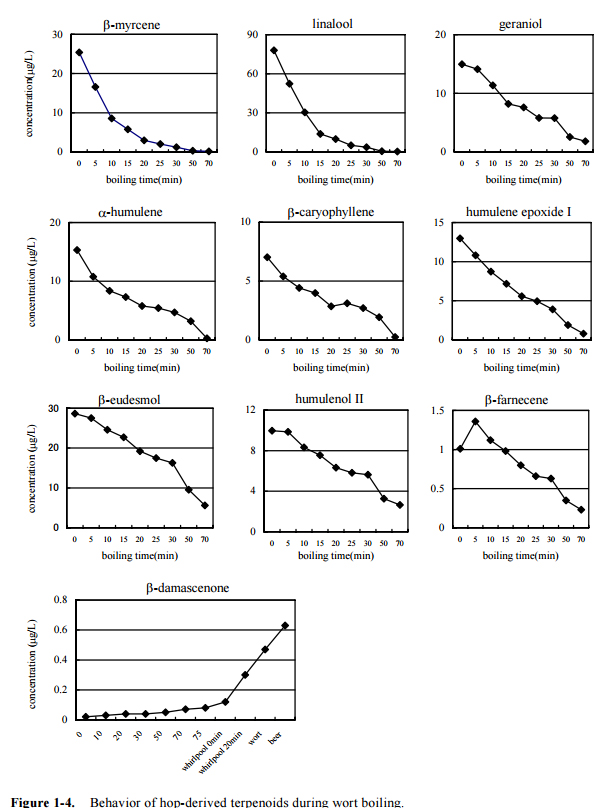

A 2013 study titled, “From Wort to Beer: The Evolution of Hoppy Aroma of Single Hop Beers produced by Early Kettle Hopping, Late Kettle Hopping and Dry Hopping” sheds some light on how the fermentation process affects hop volatiles. My understanding of their results shows a big decrease in hop oils studied throughout the brewing process, with the majority of hop oils decreasing after the fermentation process. 2

The researchers took wort and beer samples at different times throughout the brewing process and immediately stored them at -4F until they were examined. The first set of charts below shows that the floral oils compounds (like myrcene) “significantly” decreased as a result of fermentation. On the other hand, linalool seemed to show the greatest ability to stick around during fermentation, but still decreasing nearly in half. The second set of charts shows that the noble or spicy hop oil compounds also decreased significantly during fermentation and nearly disappeared after centrifugation (which suggests to me that the yeast seems to strip some of these volatile oils as it is separated from the beer). The overall conclusion from this analysis was that fermentation and centrifugation were identified as the crucial processes steps for decreasing hop oil compounds.

Fig 1A (from Dresel, Praet, Opastaele, Van Holle, Van Nieuwenhove, Naudts, Keukeleire, Aerts, and Cooman)

Fig 2 A (from Dresel, Praet, Opastaele, Van Holle, Van Nieuwenhove, Naudts, Keukeleire, Aerts, and Cooman)

Abbreviations

w/o hops: after 15′ boiling – just before early hopping

after EH: after 75′ boiling – just before late hopping

after LH: after 5′ cooling

before ferm: after 10′ cooling – just before fermentation

after lag: after lagering – just before centrifugation

after past: after pasteurization

beer ND: bottled beer without dry hopping

Biotransformation of Hop Oils

Biotransformation, which is the transformation of hop oils in the presence of yeast, is a fascinating processes. I was surprised to find a study titled, “Biotransformation of hop aroma terpenoids by ale and lager yeasts” dated all the way back to 2003, considering this is still not something you hear very often in the homebrew community today (at least I don’t). The study looked at brewing yeast (both lager and ale) ability to transform terpenoids. Specifically, they looked at geraniol, linalool, myrcene, caryophyllene, and humulene.

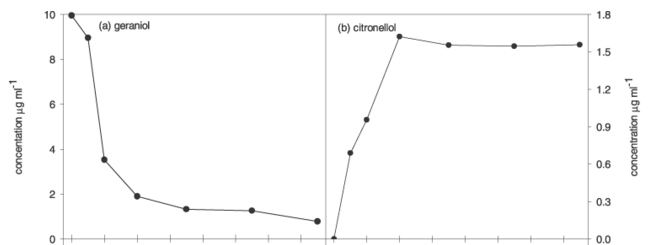

The study found that yeast does in fact have the ability to transform terpenoids. Specifically, geraniol was converted into citronellol (which is described as having a sweet, rose-like, citrus and fruity aroma) and linalool was converted into terpineol (which is described as having lilac like aromas). Remember that linalool had the greater ability to stick around the longest during the brewing process. Interestingly, they found that “most of the terpene alcohols were lost from the fermentations within the first few days of the fermentation, and after that, the decreases occurred at much lower and steadier rates…This indicates that the loss of terpenoids was associated with the increase in yeast biomass.”3 This might suggest that if dry hops are added after the first couple days of the most active fermentation, the biotransformation process would decrease. Maybe we should we should be pre-dry hopping our beer (adding dry hops to the fermenter before the wort and yeast) to take the greatest advantage of both the biotransformation process as well as the greater hop oil extraction due to not being introduced to the wort during the boil?

You can see from the two charts below the biotransformation by the ale yeast (S. cerevisiae). Although its cutoff in the charts, the bottom line represents time (days) during fermentation. It’s amazing to see geraniol basically disappear during fermentation and transform into citronellol!

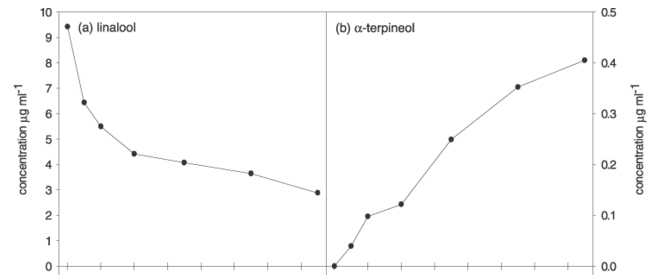

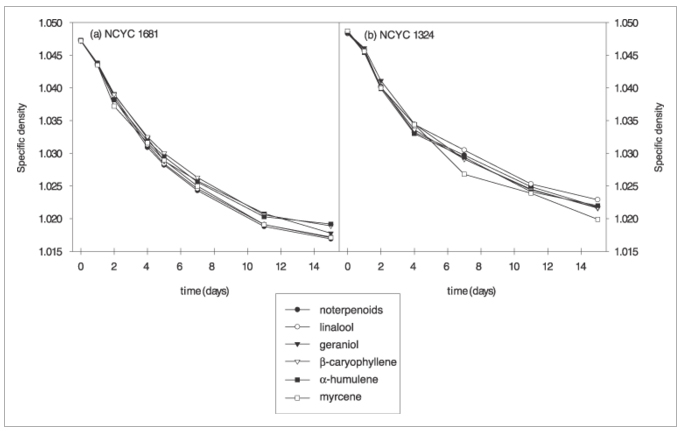

Although probably not the point of the experiment, one item I found interesting was that the large doses of terpenoids used in their process seemed to slow down the fermentation time (see the chart below). In other words, because the level of terpenoids was higher than you would typically find in hopped wort, the fermentation time was slower than you would typically expect (it took all of 15 days to reach final gravity). While it’s not clear to me what levels are considered normal in hopped wort, I’m curious if this would imply that pre-dry hopping wort might result in a slower ferment? In my few tries with the process, I haven’t noticed much of a different in fermentation time however.

It seems logical to conclude then that if you’re looking to get a more predictable “out of the bag aroma” from hops, it might be best to avoid biotransformation and to dry hop after fermentation or after the beer has been removed from yeast cake. This would also have the added benefit of reducing loss of oils by yeast cell membranes, which can “act as a fining agent” thus removing them from solution.

Introduction of Oxygen When Dry Hopping

I’m guessing that most homebrewers don’t think much about oxygen getting into their beer with the addition of dry hops, but a thesis by Peter Harold Woolfe, titled, “A Study of Factors Affecting the Extraction of Flavor When Dry Hopping Beer,” notes that the introduction of dissolved oxygen is “inevitably introduced” when dry hops are added to beer “resulting from the multitude of crevices inherent to their anatomy.” We all know that oxygen is the enemy of fresh beer! So what is the best way to limit this pickup of oxygen? Woolfe suggests that dry hopping early in fermentation while the yeast is still present and active would allow the oxygen to be metabolized by the yeast before it could oxidize the beer.4 We also know this would also have the added effect of biotransformation of geraniol to citronellol and linalool to terpineol.

A second method suggested is to add the dry hops to a vessel and then fill the vessel with C02 to remove any oxygen. In the homebrewers case, this would mean adding the hops to a purged keg, before racking the beer into the keg, removing any oxygen present. You would then rack the beer into the keg from the fermenter, ideally with a closed transfer. It’s also worth noting an additional benefit of keg hops I have experienced, which is a strong correlation of increased hop aroma detectability when additional dry hopping is done in the keg.

A quick side-note from the thesis that I found interesting was the idea of reusing hops that were used as dry hops. The thought goes that although the oils from the hops have been extracted during the dry hopping process, their alpha acid composition is still largely intact. We could then entertain the option of reusing dry hops in the boil as a way to get the bitterness and bitterness only into beer. The author couldn’t locate any brewers who actually did this however, so I just gave it a shot in my last beer! As the pictures shows, I gently squeezed the used dry hop bag a little to get the old beer out and then dumped them right into the boil. I can say the wort smelled and tasted very similar as to using fresh hops, so we’ll see how the finished beer comes out!

A quick side-note from the thesis that I found interesting was the idea of reusing hops that were used as dry hops. The thought goes that although the oils from the hops have been extracted during the dry hopping process, their alpha acid composition is still largely intact. We could then entertain the option of reusing dry hops in the boil as a way to get the bitterness and bitterness only into beer. The author couldn’t locate any brewers who actually did this however, so I just gave it a shot in my last beer! As the pictures shows, I gently squeezed the used dry hop bag a little to get the old beer out and then dumped them right into the boil. I can say the wort smelled and tasted very similar as to using fresh hops, so we’ll see how the finished beer comes out!

If you decide to give this a shot as well, don’t forget that your oil extraction would be very low if non-existent since the dry hop processes already took place. However, if you plan on adding your bittering hops early in the boil, you’d be losing most of these oils anyways (per the Kishimoto study), so why not give it a shot!

Dry Hopping Contact Time

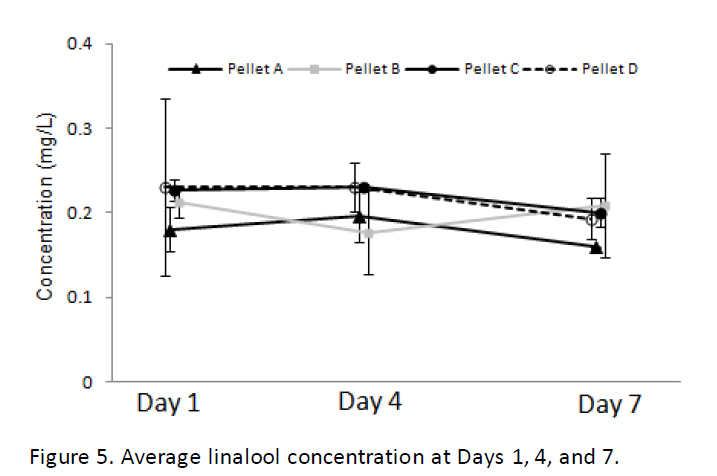

Now that there is evidence to suggest that hop oils added to the boil are largely volatilized and the yeast further strips these oils during fermentation, its clear dry hopping it’s going to be a main method of getting these glorious hop oils into the finished beer. So what is the ideal dry hop contact time to get the most from our hops? Researchers looking at the extraction rate of aroma compounds during dry hopping took a solution consisting of filtered water and ethanol in flushed cornelius kegs with 1/3rd pound/barrel cascade hops placed in a mesh bag and sunk to the bottom of the keg with stainless steel weights (similar to how many homebrewers conduct dry hopping). They then measured the oil concentrations at various days throughout the dry hop (it’s important to note that the kegs were not agitated during the their test). They found that the concentrations of oils were either near the same level as day one or had even fallen slightly, with the exception of geraniol.5

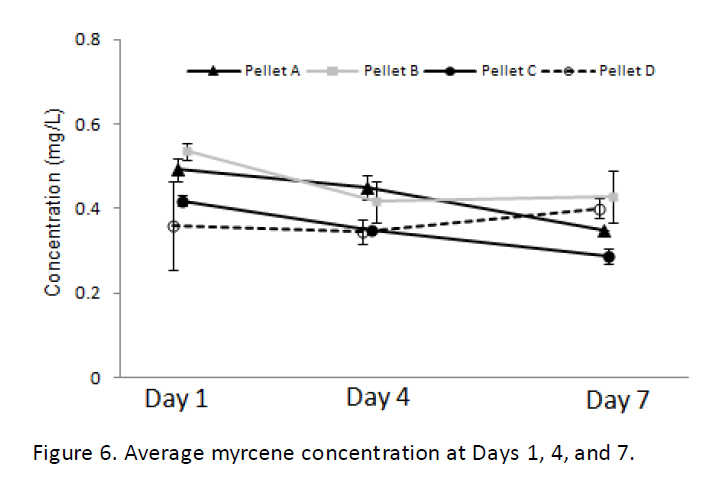

Here we can see their results, which show the concentration of linalool tested at 3 different stages of the dry hop (day 1, day 4, and day 7). Interestingly, the oils were almost completely extracted on the first full day of dry hopping and even decreased after day 4! Nearly identical results were found when the myrcene concentration levels were tested (second graph), with myrcene dropping after day 1.

The A-B-C-D groups in the above charts represent different diameter pellet hops from different producers.

Pellet Label | (mean diameter)

D | 1.72 mm

C | 1.37 mm

A | 1.09 mm

B | 0.95 mm

Dry Hopping – Pellets vs. Whole Cones

Another study examined the extraction rate of beer dry hopped with pellets vs. whole hop cones. The researches found that “more rapid extraction and greater final amounts of hop aromatic compounds” with pellets as “compared to dry hopping with whole cone hops.”6

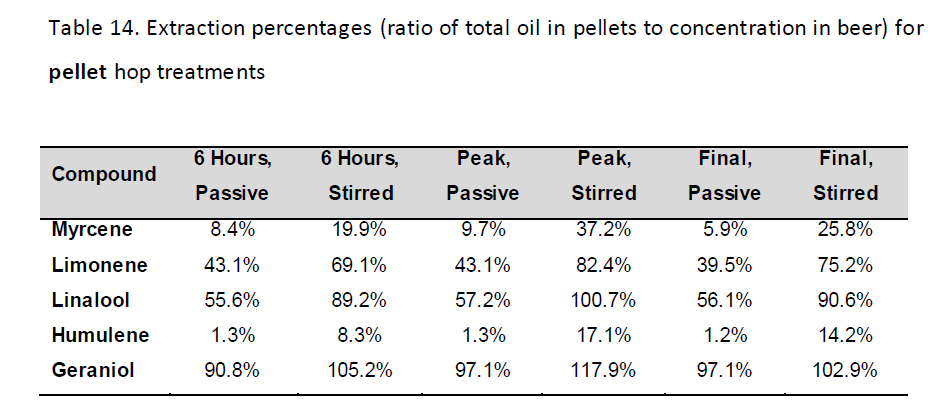

In this same study the researchers also looked at the extraction rate of hops by hour (not days) in both a stirred vs non-stirred vessel used for dry hopping. Stirred basically means the hops were added to a conical fermenter and a pump pushed the wort in and out of the tank creating a whirlpool. Below is a chart from the study showing the extraction percentages of the hops oils of pellets. You can see that circulating the beer greatly increased the extraction percentage of the hop oils (within hours) but with a greater increase in polyphenols (which may have a potential downsides like increased “bitterness, astringency, and possible oxidizing agent”). It’s interesting to see that the unstirred method of dry hopping, which is more practical to homebrewers, suggests nearly full extraction potential of the hops is basically reached in just 6 hours!

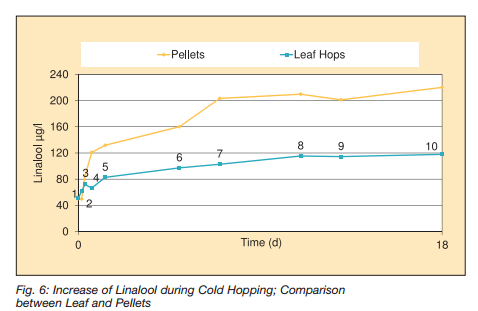

A study by Hopsteiner titled, “Dry Hopping – A Study of Various Parameters” also looked at the issue of pellets vs. leaf hops in dry hopping. They furthered the notion that pellet hops have increased extraction potential of hop oils compared to leaf hops. In this case the researches looked at linalool and you can see from the chart below that pellets achieved nearly 50% greater extraction of linalool and within just a couple days. 7

This Hopsteiner study also examined the extraction of linalool in beer dry hopped with pellets loosely vs. contained in a finely woven sack. The beer dry hopped loosely had nearly 50% greater extraction than the beer dry hopped with the use of a hop sack! This suggested that it’s possible we could get by dry hopping with far less hops if we don’t contain them in a bag. For this reason, I’m going to begin experimenting with loose dry hopping in a keg with the method described in detail here. In addition, I don’t use a bag when adding hops to primary either to hopefully achieved more extraction.

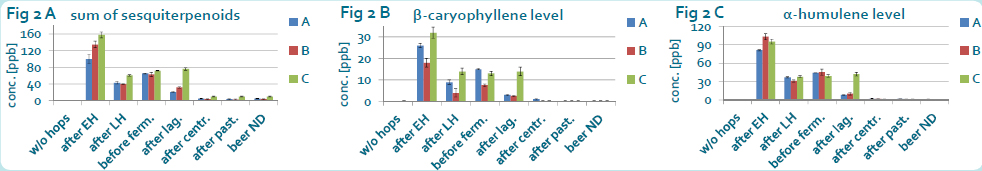

Dry Hopping and Alpha Acid Extraction

The Hopsteiner study referenced above found that dry hopping does increase the alpha acid content in the finished beer, but there was no change in iso-alpha acid (which occurs during the boil). They found the increase in alpha acids by dry hopping was around 6%, which I interpret as meaning a large alpha acid portion of the hop still has bittering potential. If this interpretation is correct and if you choose to try bittering your beer with used dry hops as discussed above, you would have to slightly adjust your bittering hops to reflect the slight drop in bittering potential due to the small extraction of alpha acids during the dry hop.

Figure 4 (from Mitter, Cocuzza, 2013)

It seems logical to me that dry hopping beer could influence the perception of bitterness in a beer, but does this increase in alpha acids to the beer actually add bitterness? The W. M., & S. C. study mentioned above found that alpha acid concentration dose not correlate to increased bitterness beer. Specifically, the researchers found that “alpha acid concentrations as high as 28mg/L in beer were not detected as being bitter by beer drinking consumers as well as a trained panel.” So you can see that although the very small amounts of alpha acid (averaged 3.7 mg/L) introduced in the beer by dry hopping found by Hopsteiner does not actually translate into increased bitterness (it may help with head retention however).

Final Thoughts

- A large portion of hop oils are removed or altered during the boil and during during fermentation.

- Do your best to avoid any oxygen pickup in your beer when dry hopping. Since oxygen is “inevitably introduced” when dry hopping, dry hop early in the fermentation process to scrub this oxygen pickup. Or try adding the hops to a C02 purged keg to remove any oxygen present on or in the hops.

- If you want to take advantage of biotransformation, which can lead to more of a rose/citrus/fruity aroma from the conversion of geraniol to citronellol, add dry hops early in the fermentation process while the yeast are still present and active.

- If you’re looking to get an “out of the bag” aroma with your dry hops, it might be best to add these after the yeast is removed or at least after the bulk of fermentation.

- It looks like long dry hop times aren’t necessary and may actually reduce the amount of oil extraction in your beers! Even without agitating your beer during dry hopping, most of the oil extraction is done in just a day.

- Don’t contain your hops, let them free! With 50% more extraction found in certain oils when not contained in a hop bag it makes sense to come up with ways to deal with hop material (like a stainless steel filter in your keg).

- Based on the data above on pellets ability to extract at a higher rate than whole cones, it might make sense to experiment with blending up or breaking apart the whole hops to improve extraction rates.

- Dry hopping doesn’t appear to increase the actual bitterness of beers, at least to the human palate. This is not to say it won’t influence the bittereing perception in a dry hopped beer.

- If the increase in yeast biomass has the ability to strip terpenoids, it would make sense to avoid over-pitching your hoppy beers. [Update: Further research showed it is actually possible to increase bitterness by dry hopping]

Footnotes

- T. K. (2008, July 23). Hop-Derived Odorants Contributing to the Aroma Characteristics of Beer. Retrieved from http://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2433/66109/4/D_Kishimoto_Toru.pdf

- D. (2013, May). From Wort to Beer: The Evolution of Hoppy Aroma of Single Hop Beers produced by Early Kettle Hopping, Late Kettle Hopping and Dry Hopping. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271848239_From_wort_to_beer_The_evolution_of_hoppy_aroma_of_single_hopped_beers_produced_by_early_kettle_hopping_late_kettle_hopping_and_dry_hopping

- Andrew King, Richard Dickinson (2003, March). Biotransformation of hop aroma terpenoids by ale and lager yeasts. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1567-1364.2003.tb00138.x/full

- P. H. (2012, August 7). A Study of Factors Affecting the Extraction of Flavor When Dry Hopping Beer. Retrieved from http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/34093/Wolfe_thesis.pdf

- P. H., M. Q., & T. S. (2012, August 7). The Effect of Pellet Processing and Exposure Time on Dry Hop Aroma Extraction. Retrieved fromhttp://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/34093/Wolfe_thesis.pdf

- P. H., M. Q., & T. S. (2012, August 7). Brewery Scale Dry Hopping: Aroma, Hop Acids, and Polyphenols. Retrieved from http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/34093/Wolfe_thesis.pdf

- W. M., & S. C. (2013). DRY HOPPING – A STUDY OF VARIOUS PARAMETERS. Retrieved from http://hopsteiner.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Dry-Hopping-A-Study-of-Various-Parameters.pdf

-610x915.jpg)

do you know the relationship between temperature and dry hop extraction? increases or decreases at low temperature? (5°C). Excuse me for my english!

The Wolfe thesis did reference a study by Krottenthaler titled, “Influences to the Transfer Rate of Hop Aroma Compounds During Dry-Hopping of Lager Beers,” where they saw a maximum of 3 days to get extraction when dry hopping at 32F . The Wolfe study mentioned a temperature of 73F with extraction occurring in less than a day (with a stirred dry hop). I don’t have the text of the Krottenthaler study, so I’m not sure if they circulated the beer during this phase of dry hopping (which would speed up extraction), but it seems logical to say that extraction time does seem slow down at lower temperatures.

This is truly excellent information and is sparking a whole discussion among our brew crew as to techniques and practices for the brewing of IPA, dIPA and APA. Thank you for your research. We will begin our experiments, and report back.

Glad to hear it!

Do you think that beers fermented with conan has more juicy hop flavor because the yeast is so not flocculant and this way it can help boost the dry hop flavors even more(through biotransformation)?

It seems likely that yeast flocculation can strip hop oils. A strain like Conan that doesn’t flocculate as well might actually be leaving more hop oils in the beer. So although it’s cloudy, there’s a potential for more flavor! If more yeast is in suspension, that could also help boost biotransformation, but if your adding dry hops into primary (especially if the yeast is still active) then there is all kind of yeast in there for biotransformation.

But it does slow down the fermentation (possibly). So what do you think isn’t it better to just chose a yeast strain which has really bad flocculation properties?

It hasn’t been my experience that it has slowed fermentation. I prefer strains that leave a good mouthfeel without too much of an ester profile and if it has poor flocculation, I just see that as a benefit to having potentially more hop oils in the finished beer. That’s not to say higher flocculant strains can’t still produce great hop forward beers, I’ve made some great beers with WLP002. I just see this information on yeast stripping oils as another piece of the puzzle when trying to get maximum hop flavor!

There’s a terrific amount of knwdleoge in this article!

I am curious how you view the information indicating hop oils are extracted in around a days time but your preference is to keg hop and leave the hops in until it kicks? Your other post showed high correlation to keg hopped beers and aroma. Perhaps it’s simply the initial process and not the time in contact with the beer that drives the higher aroma?

I haven’t seen a study to back this up (keg hopping might be a little specific) but it has been pretty clear in my experience that keg hops left in greatly increase the time the beer has the fresh hop aroma. So the oils are likely getting extracted within a day or so, but the constant contact at cold temperatures seems keep the beer tasting like a fresh IPA longer. You have a good question tough, if the oils are extracted, why does the extended time on beer in the fridge help. I’m not really sure! But if you smell you dry hops after your beer is completely gone in the keg, they still have a strong aroma.

it sure is an interesting field with so many differing views, especially as it relates to DH contact time (Bryndilson vs Vinnie for example, short vs long). I do agree, after either DH’ing or pulling hops from a keg, there is always still aroma. so i wonder if there is more to aroma than just the oils. perhaps that is the disconnect. oils are out after a day but there is still something giving off aroma. but it sure does make me wonder given they point in polar opposite directions.

Have you gotten any of the commonly mentioned, but not always found in actuality, “grassy” or “vegetal” aromas or flavors from excessive DH contact time? how long do you say your kegs usually last?

Have you read Parkin’s thesis on bitterness and dry hopping (https://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/51185/ParkinEllenJ2015.pdf)? I think she found that, after dry hopping, the impression of beer’s bitterness was higher but the amount of iso-alpha acids actually decreased.

Thanks for the link to the thesis! I have not read this yet and I wish I would have stumbled across it prior to writing a researched article on this very subject (http://scottjanish.com/increasing-bitterness-dry-hopping/). I outlined a study that also found iso-alpha acids decreased from dry hopping. However, if the beer started out with a low level of IBUs, the bitterness actually increased from humulinones. Interesting stuff, thanks again for sharing, I look forward to reading this closer!

Hi! thanks for your awesome work, it’s Just astonishing to see how much i grow up aspetto homebrewer since i discover your articles. I have a (maybe stupid) question. I tried to add hop before pitching as you suggest, and it s coming out an interesting apa. Now i want to try this method with a s.m.a.s.h. Pils, but i m concerned about the long time the hop will be in contact with beer before racking into secondary, way longer than it will be with an ale, and i worry this could give to the beer unpleasant grassy flavours. What do you think?

(sorry for my english!)

Thanks for the message! How long are you planning on leaving the beer in primary? Unless the hop character itself is a little grassy, I think you should be OK. I’ve dry hopped a beer for over a 100 days before without any grassiness!

Thanks for answering to me! I plan to keep it into primary for three weeks at ten degrees(celsius) with saaz hop. Perhaps I’ll change it because of his herbal trait, maybe some new zealander hop will do the trick. Thanks again, you re truly awesome and inspirational!

Hi. Seven days would be OK for fermentation with hop biotransformation?

It might depend on when the dry hops are added. If you’re adding them late during fermentation it may not amount to much biotransformations (with glycosides anyways). If you want to encourage biotransformations, it might be best to focus on the hot-side whirlpool additions or dry hop really early, preferably with some yeast with beta-glucosidase activity.

I’ve been trying to find info on hop stands vs adding hops at the beginning of primary fermentation, and a search turned up this post – excellent info in here!

It seems to me that there would be little difference between doing a 160F-170F hop stand post-boil or instead just putting those hops into the primary fermentation vessel. I’m going to give it a shot with my next brew. It would be nice to skip the 20-40 minute hop stand if instead I can just toss the hops into my fermenter.

I’ve been thinking the exact same thing, from what i have read there seems to be no benefits to flavour from volatilizing hop oils in the boil so why not just throw all the hops in the dry hop if its going to give you your bitterness and extract the hop oils we’re after. I’m brewing an IPA next weekend so i think ill bite the bullet and give it a go. if i dont get enough bitterness i can always throw in some bittering extract. I think i will add 150g of hops prior to fermentation and 100g on day 3 when fermentation is subsiding (22L batch) but i still have some activity so i scrub off oxygen and get some biotransformation, im not a fan of the fresh out of the bag hop aroma i prefer a juicy hop aroma which is the main reason for adding the hops early on. any input is welcome

Sounds like a great experiment! I’ve never gone that high in terms of grams pre-fermentation, but I’m curious how it turns out. I know that some people complain about not getting a saturated hop sensation without whirlpool/steep hops, so I’d be curious how that part of your beer turns out as well. It might still be worth doing small bittering charge, although you can get bitterness from dry-hopping when your initial IBU is low, but it will be a smoother bitterness. I’d just make sure you build in enough supporting bitterness for the beer based on how big it is (ABV-wise). Let me know how it turns out!

Have you looked at effect of hop stand temperatures? It would seem that another ideas might be extended hop stand (6 hours?) at lower temps (100F-140F) might be good compromise?

There is a risk of DMS with long hopstands, one study extended a hot wort stand by one hour and found higher DMS concentrations from an average of around 49 µg/L to 104 µg/L in the extended hot stands (Dickenson, C. J. (1983). Cambridge Prize Lecture Dimethyl Sulphide-Its Origin And Control In Brewing. Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 89(1), 41-46. doi:10.1002/j.2050-0416.1983.tb04142.x).

Would using a different substrate such as hard cider affect these numbers? Any info would be much appreciated!

How did the beer that you bittered with the former dry hops turn out?

Unfortunately, I tried to use ale yeast built up from a can of a favorite NEIPA’ish style beer from Tired Hands, and I didn’t get a healthy enough culture (or I infected something in the process), but the resulting beer was very metallic (dumped it). So I didn’t even test the beer for IBUs, although I probably should have looking back now.

Scott – am curious if you have seen this information yet and wonder what your thoughts are – http://youngscientistssymposium.org/YSS2016/pdf/Kirkpatrick.pdf It was sponsored by New Belgium. The title is : “Optimizing hop aroma in beer dry hopped with Cascade utilizing glycosidic enzymes” by Kaylyn Kirkpatrick.

Thanks for sharing this! I haven’t read this yet, but find it extremely interesting. I’ve started researching this concept and experimenting with adding direct enzymes to try and release glycosides (which I need to write about still), it’s definitely an interesting new area of hop research with some potential.

I saw your Instagram post about the Rapidase enzyme. From what i read these enzymes are indicated to be used post-fermentation, but it looks like you may have added during fermentation. If so, why? And do I have to wait for the book to hear the results? (@Brulosophy if you are reading this…exbeeriment time!)

I actually did add the enzyme at the end of fermentation for that very reason! I’ll likely include the results in book or perhaps a separate blog post.

Thaks for the deep depth of the article. Provides a lot of insights into my beer club’s current discussion on the topic.

Scott, I’m noticing some homebrew results similar to mine. I brewed a neipa using 1318, us05 and windsor. The first dry hopping was during fermentation (in a hop bag) and the second one was free.

The thing is that the beer turned out darker than what was meant to be (almost caramel) when I bottled it.

Some people says that this effect is related to yeast and its interaction with a huge amount of hops.

I have never had an oxidation (it was my first thought)..

Do you know if there is such a relation between yeast, hops and darkening?

Thanks, cheers from Brasil!

I started to speculate why NEIPAs might be prone to faster oxidation here: http://scottjanish.com/lupulin-powder-vs-pellets-experiment/. I need to look into it further though!

Hazy NE ales oxidise very quickly and turn a muddy grey/orange colour. All hop aroma is lost and an awful sherry type sweetness permeates the smell and taste. Even tiny O2 pick up at packaging results in this. PPB <30 O2 is the aim.

Great article!

You’ve mentioned it’s best not to contain your hops, does this mean that it’s suggested to dry hop for x amount of days, cold condition with the hops still in the brew? I have been dry hopping contained so I can pull the bag out at the end of the x amount of days I plan to dry hop.

How does that effect the oil extraction seeing technically they are still in contact with the beer for a lot longer than the few days of dry hopping? (Figure 5 from above).

Thanks

If your hops aren’t in a bag, you might see a jump in measurable hop compounds, which I would assume you could always increase the dry hop amount in a bag to compensate (if you can even tell a different on the palate anyays). One reason I don’t like pulling the bag out after dry hopping is it seems like a good opportunity to introduce oxygen, especially if fermentation is complete. Currently, if I want a really hoppy beer, I’ll generally dry hop early (around day 2-3) and leave these hops in the fermenter the entire time. I’ll then follow-up with another small dry hop charge a day or two before kegging. Since I generally ferment in a keg, I can put pressure on the keg for this last dry hop charge and this allows me to swirl the fermenter gradually a few times to also encourage quick extraction.

Thanks, that does make sense and I think I’ll try that next time, however, do you see what I’m trying to ask? Figure 5 above shows the linalool concentration lower after 4 days contact time, leaving dry hops in and I would expect this to result in less flavour/aroma then if you pull out the dry hops after 4 days. I do wonder if that linalool concentration drop is only at certain temperatures though? SO if you dry hop for 4 days at 18c then cold condition for 5 days at 1c it may escape the linalool concentration drop?

Very interesting article, but I’m confused with your conclusion, or rather your conclusion (to only use dry hopping) doesn’t fit with my real world experience. I made 2 IPAs (20L), 1 with a 150g of dry hops and only 70g in the boil, the other has no dry hop at all, instead the same quantity of hops was added as a late addition (split between 5 minutes and 1 minute). The second beer was by far and away the hoppier beer. Amazing aroma and flavour. The heavily dry hopped beer was by comparison very bland. I also note that commercial breweries tend towards late additions and whirlpooling. It would be interesting to see how the breweries that are good at making hoppy beers go about achieving that huge hop flavour. It’s not by only dry hopping.

Thanks

I’ve done some more research since posting this article and done a few experiments like the one below where I only used cold-side dry hopping in an IPA and wasn’t happy with the results. I do think that hot-side hops are very important for flavor. With hot-side additions, you can get oxygenated sesquiterpenoids that can lead to more kettle flavor. These are compounds not in the beer without adding the hops at hotter temperatures. Thiols are also playing a role on the hot-side and some even increase with boiling temperatures, which is another good reason to add hops on the hot-side.

http://scottjanish.com/zero-hot-side-hopped-neipa-hplc-testing-sensory-bitterness/

Thanks Scott, awesome article. I was having a lot of trouble with too much grassy/vegetal flavor in my dry hopped IPAs, even when dry hopping in secondary for only 3 days. But – based on your article, I dry hopped my last IPA immediately after high krausen (end of day 2 after pitching in this case) and the resulting beer was MUCH less grassy – it had just the right amount of grass to give that ‘fresh hop’ flavor without being offensive. And to boot I thought it was much fruitier and complex, in a good way! I am now a total convert to biotransformation, but I have one question. Normally I like to ferment IPAs for at least 10 to 12 days, so if I add dry hops to primary on day 2 or 3, that’s 7 to 10 days of dry hopping. Is that too long? Would you recommend dry hopping for 3 to 5 days and then transferring to secondary for another 5 days? Thank you!

I typically leave the first early dry hop addition in the fermenter the whole time without any issues. I wouldn’t worry about transferring it to another vessel to dry hop again. The last addition probably only needs 2-3 days (even quicker if the fermenter is agitated) rather than up to five days.

Thanks! Sounds good, I will give it a try.

” It seems logical to conclude then that if you’re looking to get a more predictable “out of the bag aroma” from hops, it might be best to avoid biotransformation and to dry hop after fermentation or after the beer has been removed from yeast cake. ”

Hi! Could you please open little bit of that “out of the bag aroma”. That phrase leaves bit of debate that what that means. Is out of the bag aroma more like hop pellet aroma you get from pellet bag?

Thanks!

Out of the bag aroma to me is what you get after cutting open a new package of hops.

Planning a fresh hop (Cascade), Red ale and have concerns I may be wasting $$ and time by adding fresh hops at whirlpool/steep 160-170F to achieve aroma-only to be lost during fermentation (conical) for 4-5 days. Aroma would be lost, then DH would be needed. I want to avoid DH (post-fermentation) due to clogging concerns, but still maintain aroma.

Have you considered dry hopping with a filter screen or bagging the hops to avoid clogging?

Dry hopping does increase bitterness. Try it yourself: Brew a hazy IPA with no kettle hops, and 4.0 lbs/bbl of Vic Secret. You won’t even be able to drink it.

I agree! – http://scottjanish.com/dry-hopping-effect-bitterness-ibu-testing/

Is it possible to get this as a PDF publication?

Fascinating information! I’m curious about why I am sometimes getting the flavor of soap (like ivory bar soap) in my New England IPAs. It’s a bitter flavor that coats the tongue and stays there for a while. This doesn’t happen in all of my NEIPAs, so it must be only with particular types of hops. I am admittedly sensitive to linalool, which has a soapy flavor to me as described. But linalool is in almost all hops, no? And I don’t get this soapy flavor from most craft brewery’s NEIPAs. Only on occasion. When I home-brew, I add late kettle hops, hops at day three of fermentation, and hops for two days at the end of fermentation. As you mentioned in your article, could it be biotransformation of geraniol to citronellol and linalool to terpineol? I just can’t figure this out. It has happened with beers hopped with majority Citra at late kettle. Also, happened with Galaxy late kettle and during fermentation. Thanks!

Hi MIchael. What is your brew system? Are you getting a lot of trub transfer from the kettle into your bucket/carboy? Soapy flavours can come from lipids, which come from kettle trub. Some hops do have that soapy flavour, but I’ve found that it’s higher trub amounts that lead to soapy flavour in the finished beer.