Can a Once-Forgotten (and Lost) Lager Yeast Be a Good India Pale Lager (IPL) Strain?

Tum 35 was a popular lager strain until the 1950’s until it virtually went extinct. Resurrected in 2019, the strain shows promise as a soft, neutral, and low-sulfur producing IPL strain.

I

‘ve only brewed a handful of lagers throughout my entire homebrewing career (not counting copitched lager beers). We’ve brewed a few now at Sapwood, but Mike mostly came up with the recipes based on his much more extensive lager brewing history. I think I’m just sensitive to the sulfur-like aroma many lagers can have, which I feel can distract from the style’s otherwise grainy and clean characteristics. Even when throwing hops at a lager, I still find this “lagery” flavor somewhat competitive for the hop-derived flavors I’m after.

Despite my preference for ales, I have done a couple of unique lager strain experiments (mainly through the inspiration of my friend Spencer Love) like a Rice Saison Lager and Thiol Driver (a lager/wine yeast copitch beer designed to take advantage of the science of synergy and biotransformation). One of the reasons I’m so intrigued by lager ferments, however, is the potential increase in hop-derived compound retention that low-temperature ferments can provide (more on this later in the post).

When I read a newly published paper from BrewingScience about a resurrected lager strain (Tum 35) with reportedly no sulfur aroma and ability to ferment as low as 50°F (10°C), you can see why I started to get excited again for some more lager and hop experimentation!

This post explains some of the history of the discovered (again) lager strain Tum 35. I then brew (with the help of some friends) some test batches with the strain after getting a yeast slant mailed from the author of the paper in Germany (who also permitted me to write about the results). Lastly, I then brewed an India Pale Lager with Tum 35, the reason I was excited about the strain in the first place! With the help of a commercial enzyme to unlock hop-derived thiols, science into selecting the whirlpool hop varieties, and the cold fermentation ability of Tum 35, I attempted to push the aromatic thiol flavors as much as possible without the “lagery” flavors getting in the way!

Tum 35 History

All of the historical information in this post comes from the study referenced below titled, “Resurrection of the lager strain Saccharomyces pastorianus TUM 35.”

The Research Center Weihenstephan for Brewing and Food Quality (BLQ) is an institute of the Technical University of Munich (TUM) and where these strains are studied and banked (thus the TUM names for the strains). Let’s start with Tum 34 as it’s the most popular lager strain used in the world and one of the first bottom-fermenting strains to be sequenced and published.1 While Tum 34 may not sounds familiar, Frisinga Tum 34/70® probably does ring a bell (often referred to as 34/70 Weighenstephan 34/70, W 34/70).

The lager strain Tum 34 started to become the dominant player in the lager game in Bavaria, Germany, in the later 1950s due to its superior ability to flocculate and produce clean beers despite lousy weather at the time producing unreliable malts low in amino acids and soluble proteins. After World War II, however, Tum 35 was one of the more common and widespread yeast strains used in Franconia (northern Bavaria); it was then referred to as “C” because of the city and brewery of it’s use-Hofbrauhaus Coburg. At the time, beers brewed with Tum 35 were described as “mild, balanced flavor, and fine notes of hops.”

As mentioned, bad weather in the early 1950’s started to produce less than ideal grains used for brewing. The weather seemed to have the most significant impact on the Tum 35 strain, as brewers were having a difficult time harvesting the lager strain as it would stay in suspension much longer than others (even after crashing). In fact, of all the strains used at the time, Tum 35 was reportedly one of the worst flocculators. Frustrated, brewers started to turn away from Tum 35, despite enjoying their characteristics from the strain. Bavarian lager brewers began to use other more reliable harvesting strains like Tum 44 and eventually transitioned to Tum 34 because of better-reported flavor consistency.

Tum 35 was completely forgotten about from the late 1950s to the present day, only being used in 1987 and 2002 in two published strain comparison papers (by Donhauser et al. and Wagner). Tum 34 wasn’t even active as a slant agar or cryo stock culture. So, after that last use in 2002 for academic purposes, Tum 35 was essentially lost; fortunately, a forgotten box in a storage room was recently found at the Institute of the Technical University of Munich that was marked “35.” The researchers were able to reactivate the yeast from a dried pellet in liquid wort and confirm it was, in fact, Tum 35.

Tum 35 Studied

After finding the forgotten lager strain in a box and resurrecting it, the researchers began putting the strain to the test against other lager strains. In their 2019 paper, the authors brewed an ~8 gallons (30 L) test batch where fermentation was done at 52°F (11°C) for 13 days with a diacetyl rest to follow. After subsequent lagering for two weeks, the beer was put in front of a trained tasting panel where the results were compared to 480 other lager beers tasted by the tasting panel throughout 2018.

Tum 35 preformed admirably as the comparative results showed the strain was above average in flavor, taste, and quality of bitterness. The panel described the beer fermented with Tum 35 as “pure and delightful, fresh and yeast-typical, full-bodied with a slight bitterness, well balanced and soft.” Most interesting to me, the strain was determined to have no sulfuric aromas that are often typical of lager strains.2

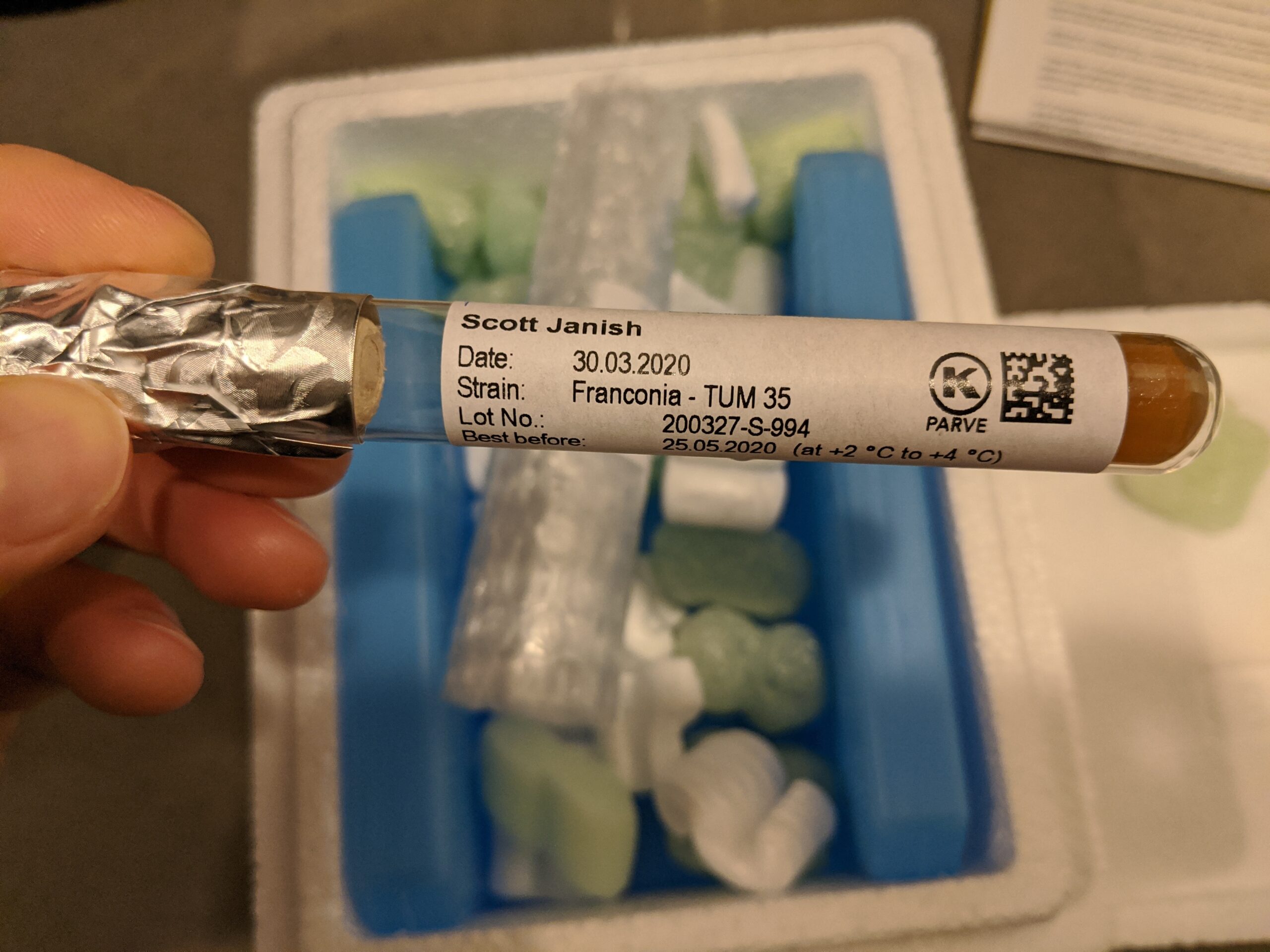

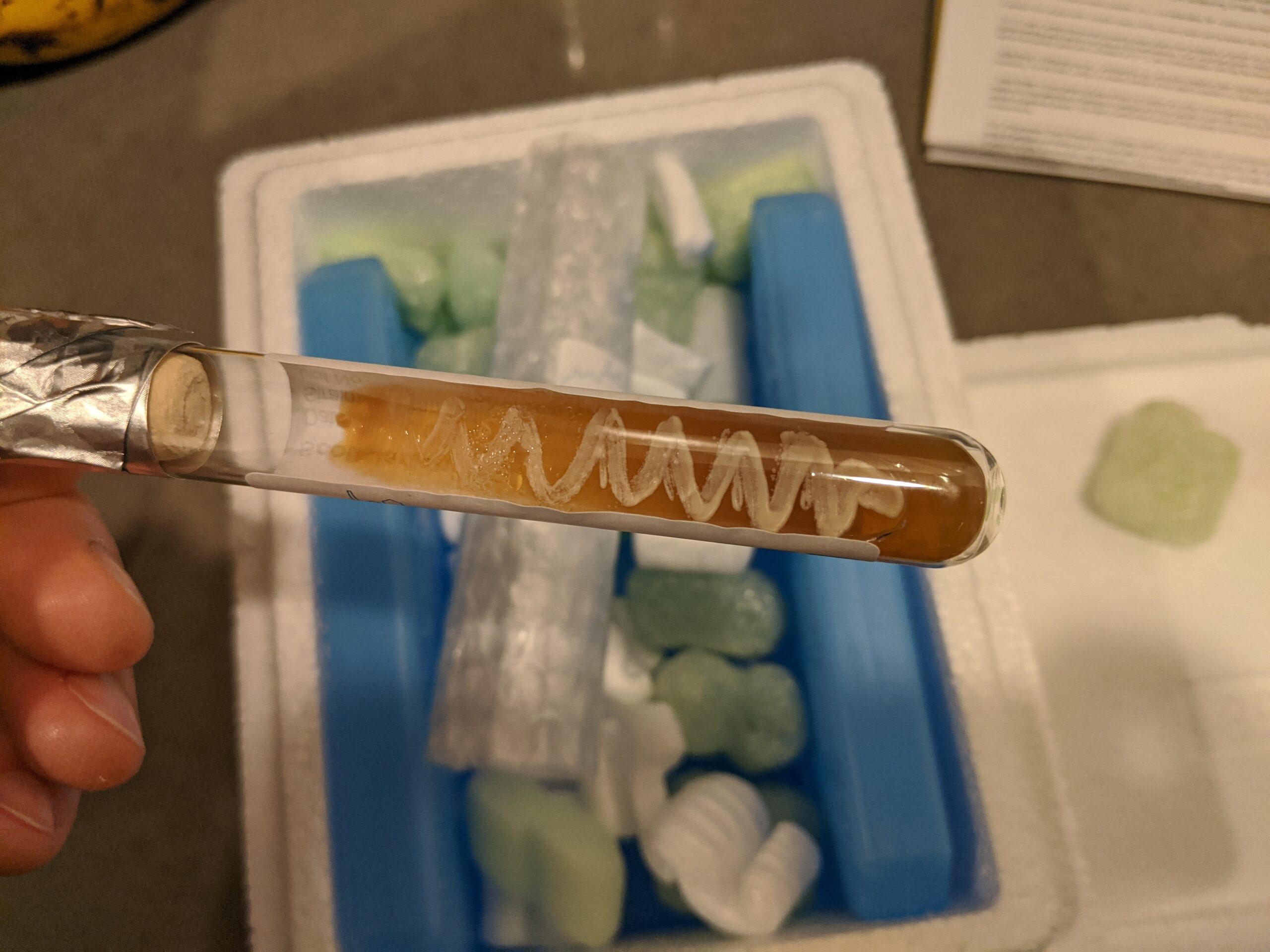

With a low sulfur-producing lager strain that can be fermented cool, has a soft and full-bodied mouthfeel, and tastes “delightful,” you can see why I requested a sample be shipped from Germany to start experimenting with! After delays due to the COVID, which impacted the needed certificates necessary for delivery to the USA, I eventually got a yeast slant in the mail.

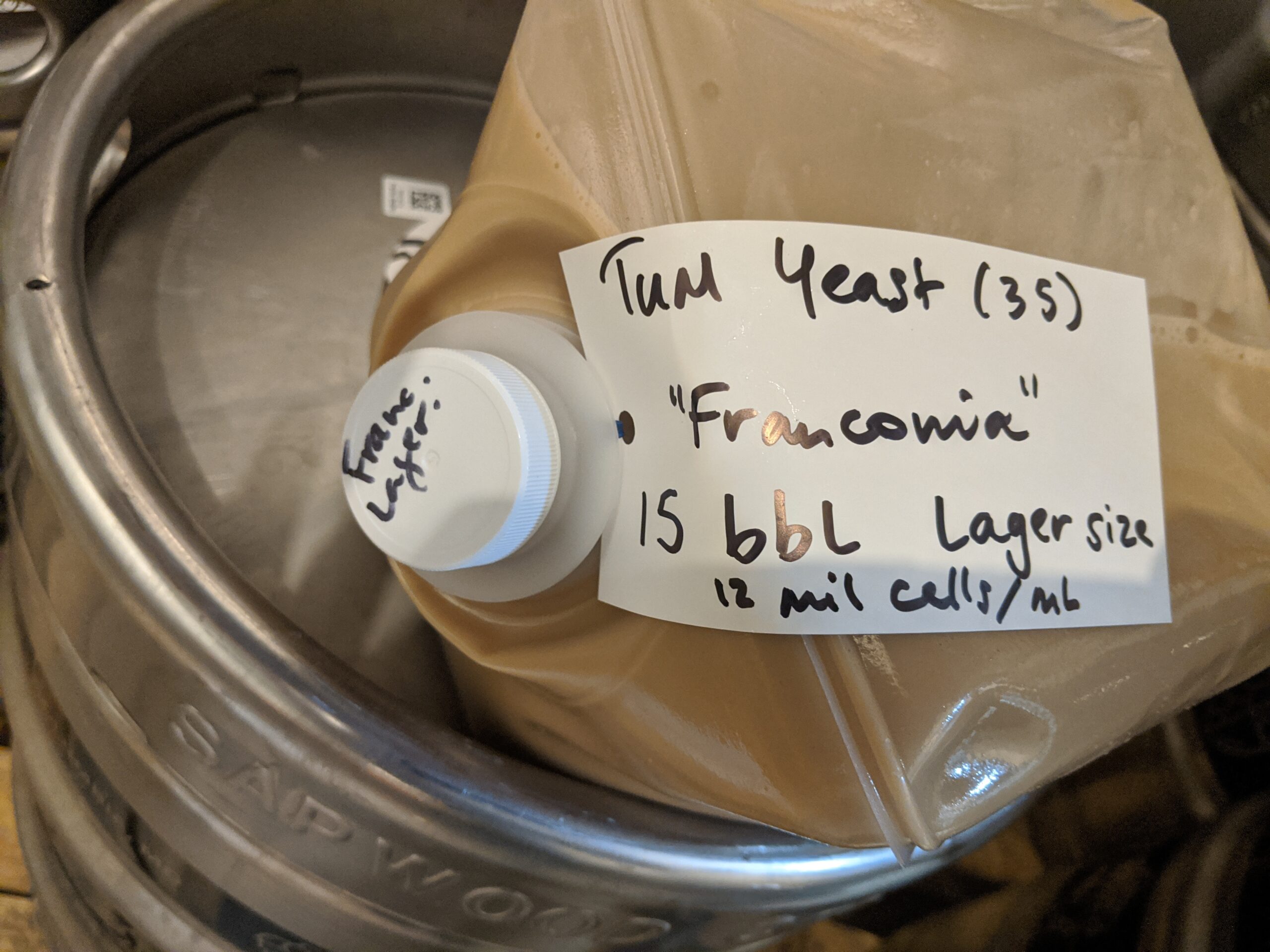

Having never propped up a strain from a slant, I sent the Tum 35 (now called and referred to as JY268 Franconia strain) to Jasper Yeast in Virginia. Jasper banked the strain for future use for us (and you!) to use at Sapwood and built up a pitchable culture for me to experiment with for this post. If you are interested in experimenting with the Franconia lager strain, you can reach out to Jasper to get a pitch. I’m curious what others might think of the strain!

Hop-Derived Fruity Thiols and Cold Ferments

Before I go further, I need to explain a little science that has me so interested in a lager strain with NEIPA-like mouthfeel descriptors. A 2017 paper experimented with how different fermentation temperatures might impact the retention of more hop-derived fruity thiols. Thiols have very low taste thresholds, so even small amounts of retention could have a significant aromatic impact on beer. I talked a bit more about thiols midway through this post on hot-side hopping if you are interested in more background thiol information. In this case, the authors found that the colder a beer fermented, the more retention of hop-thiols remained in the beer.

Specifically, the paper mentioned above brewed test beers with Mosaic hops at the onset of fermentation and measured thiols 3MH and 3MHA. The authors found that almost twice the amount of 3MHA was measured in the beer fermented at 59°F (15°C) compared to the one at 71°F (21°C) with a wheat beer yeast (Tum 68). Specifically, the tropical and desirable 3MHA (which is converted from 3MH) went from 4 ng/l to 8 ng/l at the lower temperature. This might not seem like much, but with a low threshold for 3MHA (9 ng/l), you can see why it’s important.

Also, because 3MHA is converted from 3MH, it’s equally important that the 3MH concentration also increased when fermented at the cooler temperature going from 31 ng/l to 37 ng/l.3 Obviously, the more you can push the 3MH the more potential for 3MHA (especially with the right yeast strain or with a commercial enzyme).

So, what if we take advantage of low temperature fermenting lager strain to potentially retain more fruity hop thiols from the hot-side whirlpool hop additions as well as add a commercial enzyme to the wort to increase thiols even further potentially.

Before I go straight into brewing the test India Pale Lager with the Franconia strain, we put it to the test in some more standard lager worts with some friends’ help. This way, we all got a more hands-on sense of how it compares to other lager strains we’ve brewed with in the past. It’s also just nice to not rely entirely on the academic sensory results.

Tum 35 Test Batches

First, my good friend Trevor Fisher brewed a split batch experiment with his Grain Father. Here, he brewed two identical lagers, but one was fermented with Tum 35 (built up from Jasper) and the other with Tum 34 (34/70 dry yeast packet). The recipe was inspired, in part, from an Oxbow beer called Luppolo, which is a lightly dry-hopped unfiltered lager.

After fermentation and four weeks of lagering, I went over to Trevor’s house to do a blind triangle test of the beers while he still had them on tap. I was served two samples of the 34/70 fermented beer and one sample of the Tum 35 (Franconia) fermented beer. I was able to detect the odd beer out. For me, it was both in the aroma and taste where the beers were distinguishable.

As advertised, the distinguishing trait in the Tum 35 beer was a less “lagery” aroma (I’m already a fan). The 34/70 beers had a fruity green-apple-like mid-palate that wasn’t in the Tum 35 beer. Overall, the Tum 35 beer was more neutral, with a little more noticeable minerality and softer mouthfeel. The aroma from the Tum 35 beer seemed to be coming mainly from the pilsner malt used. There was very little yeast-derived fermentation flavors/aromas that I could detect. There was a little more alcohol hotness in the 34/70 beer, likely due to a two-point lower attenuation from the Tum 35 beer. Trevor got a final gravity of 1.010 with 34/70 and 1.012 with Tum 35. Of all the test batches, Trevor had the best luck getting a lower FG with Tum 35, perhaps we should of all pitched closer to his rate of 200 mL of slurry into 3.5 gallons or wort with elevated fermentation temperatures!

Spencer, who brews an easy-drinking lager once a year to take to a lake cabin to consume with his friends responsibly over a weekend, also tested out Tum 35 with his lake rice lager for the year (it’s also the slurry I used for the IPL in this post).

Spencer’s lager was another excellent example of how Tum 35 can be a slow fermenter, especially at colder temperatures. For his rice lager, he maintained 50°F (10°C) for the entire ferment, not even rise at toward the end of fermentation (something he would do the next time around to help it finish out a little quicker and perhaps lower the gravity). The beer eventually achieved 68% apparent attenuation, but it took a while. For example, the following are his gravity readings throughout the ferment.

————————–

Tum 35 Rice Lager Fermentation Readings

Starting Gravity: 1.041

5 days: 1.034

8 days: 1.024

11 days: 1.016

15 days: 1.014

19 days: 1.013 (FG)

————————–

Spencer’s results (like ours at the brewery with Tum 35) suggest that a good big healthy pitch and slightly warmer temperatures are probably best to get the strain to finish in a more reasonable time frame. After our test batch experience, I’d probably start Tum 35 at 52°F (11°C) and gradually ramp to 58-60°F (14-15°C) over a week or so. It doesn’t appear to be the most attenuative strain either (which can be a good thing depending on your goal) as the rice lager finally finished at 1.013 but was mashed low at 149°F (65°C). Maybe even having an active starter and larger yeast pitch would help (this was from our commercial pitch that sat around awhile before using).

Overall, Spencer’s sub 4% Tum 35 lager was super drinkable. Head retention was decent but not spectacular. There was a more pronounced malt character than he was expecting (cracker, biscuit, and straw-like). Regarding the sulfury-lager notes, he too thought the strain was on the low end of the flavors. The cleaner ferment is probably why the malt flavors shined so much (something we found also).

Both Trevor’s and Spencer’s recipes are available below.

Blank

Your content goes here. Edit or remove this text inline or in the module Content settings. You can also style every aspect of this content in the module Design settings and even apply custom CSS to this text in the module Advanced settings.

Trevor's Pilsner Experiment Recipe

Malts

68.4% — Mecca Grade Estate Malt Pelton: Pilsner-style Barley Malt — Grain — 1.8 SRM

26.1% — Weyermann Barke Pilsner — Grain — 1.8 SRM

4.7%) — BestMalz Chit Malt — Grain — 1.3 SRM

0.9%) — Weyermann Caramunich II — Grain — 63 SRM

Miscs (RO Water)

1.25 g — Calcium Chloride (CaCl2) — Mash

1.25 g — Canning Salt (NaCl) — Mash

2 g — Epsom Salt (MgSO4) — Mash

2.1 g — Gypsum (CaSO4) — Mash

8.5 ml — Lactic Acid 88% — Mash

Mash

Protein Peptidase — 126 °F — 10 min

Temperature — 151 °F — 40 min

Mash Out — 171 °F — 10 min

Hops

2.5 oz (22 IBU) — Tettnang 3.5% — Boil — 60 min

1.75 oz (15 IBU) — Tettnang 3.5% — Boil — 45 min

1.25 oz (1 IBU) — Hersbrucker 2.3% — Aroma — 20 min hopstand @ 180 °F

1.25 oz (2 IBU) — Tettnang 3.5% — Aroma — 20 min hopstand @ 180 °F

Dry-Hops

0.53 oz — Tettnang 4.5% — Dry Hop — day 2

0.53 oz — Tettnang 3.5% — Dry Hop — day 2

1.2 oz — Hersbrucker 2.3% — Dry Hop — day 10

1.2 oz — Tettnang 3.5% — Dry Hop — day 10

Yeast

Fermentis W-34/70 and Tum 35

Fermentation

Primary — 53 °F — 7 days

Primary — 58 °F — 3 days

Conditioning — 33 °F — 14 days

Spencer's 2020 Lake Light Rice Lager Recipe

Malts

American – Pale Malt (6 Row) US 38.1%

German – Pilsner (Weyermann) 28.6%

American – Rice, Flaked (Briess) 19%

German – BEST Chit Malt (BESTMALZ) 9.5%

Hops

0.20 oz Saaz Mash

0.80 oz Saaz 60-minute

1 oz Saaz 5-minutes

Mash

148 °F

Yeast

Tum 35 @ 50°F

Tum 35 India Pale Lager Recipe

Brewed: August 2020

Tasting notes: September 2020

Batch size: 5.5-gallon

| OG/FG/ABV | Est. IBU | SRM | Water | Mash Temp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.085/1.028/7.61% | 101 | 5.0 | ~150 ppm chloride and 100 ppm sulfate |

158°F

|

| Grain | Percentage |

| 2-Row (Rahr) | 45% |

| Pilsner (Weyermann) | 20% |

| Chit Malt (BESTMALZ) | 10% |

| Malted Naked Oats (Crisp) | 10% |

| Malted Red Wheat (Rahr) | 10% |

| Maltodextrin | 5% |

| Hot-Side Hops | Amount | Timing |

| 2018 Nugget | 15 grams | Mash Hops |

| 2019 Mosaic | 85 grams | Whirlpool – 185°F (85°C) |

| 2018 Nugget | 70 grams | Whirlpool – 185°F (85°C) |

| Dry-Hop | Amount | Timing |

| Nectaron® (Hort 4337) | 60 grams |

Day 1 of fermentation (at yeast pitch)

|

| 2019 Galaxy | 200 grams @ 52°F (11°C) |

18 days post yeast pitch (in a sealed and purged keg)

|

| Nectaron® (Hort 4337) | 100 grams @ 52°F (11°C) |

18 days post yeast pitch (in a sealed and purged keg)

|

| Enzymes | Amount | Timing |

| Scott Lab’s Revelation Aroma | .4 grams | Yeast Pitch |

| Scott Lab’s Expression Aroma | .4 grams | Yeast Pitch |

| Yeast | Temperature | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Tum 35 (JY268 – Franconian Lager) | 52°F (11°C) | 18 days |

Results

Now that I had the opportunity to taste a couple of Tum 35 test batches, I was excited to see what the strain could do in a low-temperature ferment with hops and enzymes designed to boost (and hopefully retain) fruity monoterpene alcohols and thiols.

For the yeast, I pitched ~ 300mL of Tum 35 harvested from Spencer’s trials. I kept the beer at 50°F (10°C) for the first two days of fermentation, but with little activity seen in the airlock, I bumped (and kept the temperature) to 52°F (11°C) for 16 days before kegging and dry-hopping.

Because I planned on pitching two commercial enzymes with this IPL for biotransformation potential, I also decided to add 2-ounces of hops at yeast and enzyme pitch to push the compounds that might be converted (paired with the low fermentation temperature this seemed like a good idea to try and retain and boost thiols). Also, the whirlpool additions were lowered to 185°F (85°C) in hopes of additional hop-derived oil retention and potential conversion.

As for the whirlpool hop selections for this beer, Mosaic was incorporated as it was found to be a very high survivable hop, something I’ve become more convinced makes a difference for saturated hot-side flavor. In addition, it’s a variety we’ve continually found at the brewery to be a great hot-side hop in terms of carrying through some its flavor/aroma after fermentation.

Regarding Nugget, a 2015 BrewingScience study looked at extraction efficiency of hot-side hops and tested for 59 different hop compounds for fifteen single-hopped beers. Of the 15 different hop varieties tested, those that imparted the most monoterpene alcohols were (in order of highest): Nugget, Columbus, Cascade, Centennial, and Sorachi Ace.4 This is likely due in part to the high concentration of linalool in Nugget, one of the compounds included in the set of survivables studied by Yakima Chief.

You might wonder why I used a slightly older (2018) lot of Nugget, I’m a fan of experimenting with slightly older hops in the whirlpool (along with fresher hops for greater overall complexity of compounds going into the fermenter). One reason is that a 2014 paper found a reduction in hydrocarbons as hops aged (these are the greener, more resinous, and woody compounds). In the study, five U.S. varieties (Columbus, Chinook, Nugget, Cascade, and Mount Hood) in bags were cut open and stored at room temperature or 32°F (0°C) and analyzed after four and twenty-four weeks for compound concentrations. The authors found a shift in the percentage of terpene hydrocarbon percentages. Specifically, in fresh hops, the terpene hydrocarbons accounted for approximately 85-95% of the hop oils; after twenty-four weeks of storage exposed to air at room temperature, the percentage dropped to 30-60%.5 Although these hydrocarbons are generally more volatile and likely have little staying power when introduced to boiling wort, I suspect at chilled whirlpool temperatures, they may be finding their way into wort at higher rates.

Tasting the IPL two weeks after yeast pitch, I was thrilled with the amount of post-fermentation hop aroma and flavor. How much of this was due to the early 2-ounces of Nectraon, low-fermentation temperature, whirlpool hop additions, or enzymes is unclear. Still, there was a great mango, apricot, and jelly donut-like already before dry-hopping, providing a great hop saturated base layer for some dry-hopping! There was also a surprisingly high pH after primary and pre-dry-hop at 4.52 (unfortunately, I never recorded a post-fermentation dry-hop pH).

Nectaron® (the experimental name was HORT4337) is a new promising hop from New Zeland that is described as super tropical and passionfruit-forward. After a few little test runs with it at the brewery, sampling a friends, and smelling from the bag I get a subtle Galaxy-like bubblegum thing, so why not pair them up! I want to experiment further with Nectaron® as well as get a glimpse into its oil data to potentially get a sense of when to best use the strain (whirlpool, early dry-hop, late dry-hop, etc.).

For dry-hopping, I transferred out of the primary fermenter in a closed-loop into a purged keg (with a dip tube filter) and put back into the keezer at 52°F (11°C) for three days. Once a day, I would pick up the keg and give it a good swirl to encourage the hops to get back into suspension and extract (the keg was under ~15 psi of pressure during the dry-hop). After the three days of cool dry-hopping, I transferred to a purged serving keg and put on tap at ~38°F (3°C).

Overall, I was pleased with this beer! As advertised in the literature and found in our test batches, Tum 35 produces very little of the lager-like sulfur aroma I’ve become sensitive too, which I think does allow the hops to stand out more. Despite the beer finishing sweet (1.028), it gives a much dryer and crisp impression but still a nice hazy IPA-like softness. Because Tum 35 appears to produce beers very neutral on the palate (not a lot of big fermentation phenols or esters), it then seems to enhance the flavors coming from the grain (probably especially at such a high final gravity).

Whether it’s the slow fermentation retaining more hop-derived thiols, some biotransformation, neutral and soft Tum 35 ferment, or just some great hops, it was a solid IPL! Despite being sweet, it wasn’t as cloying as some hazy IPAs can be. To me, I could still slightly tell it was a lager, but it didn’t scream it like other IPL’s I’ve had. There seems to be some promise in this once forgotten lager strain. If our little bit of experience with Tum 35 is accurate, it seems to be a slow fermenter (taking around two-weeks to finish) and isn’t super attenuative either. Granted, in this particular beer, I mashed hot and had some maltodextrin. However, we just finished fermenting a Tmavé Pivo (Czech-style dark lager)and saw ~67% apparent attenuation when mashing at 155°F (68°C).

This India Pale Lager test batch was good enough that we will be scaling a version of it up for an upcoming collaboration IPL brew with Astro Lab Brewing in Silver Spring, MD. Again, we’ll ferment with Tum 35, but mashing much lower (150°F (65°C)) to increase the attenuation. We also plan to eliminate the oats (just pilsner, malted red wheat, and chit malt) for an even more neutral base for a heavy Nelson Sauvin dry-hop and Riwaka and Wakatu whirlpool hops!

Footnotes

- Nakao, Y.; Kanamori, T.; Itoh, T.; Kodama, Y.; Rainieri, S.; Nakamura, N.; Shimonaga, T.; Hattori, M.; Ashikari, T. Genome sequence of the lager brewing yeast, an interspecies hybrid. DNA Res. 2009, 16, 115–129.

- Resurrection of the lager strain Saccharomyces pastorianus TUM 35. M. Hutzler, L. Narziß, D. Stretz, K. Haslbeck, T. Meier-Dörnberg, H. Walter, M. Schäfer, T. Zollo, F. Jacob and M. Michel. BrewingScience, 72 (March/April 2019), pp. 69-77.

- Haslbeck, K., Bub, S., Schönberger, C., Zarnkow, M., Jacob, F., & Coelhan, M. (2017). On the Fate of B-Myrcene during Fermentation – The Role of Stripping and Uptake of Hop Oil Compounds by Brewer’s Yeast in Dry-Hopped Wort and Beer. BrewingScience, 70, 159-169.

- Dresel, M., Praet, T., Van Opstaele, F., Van Holle, A., Naudts, D., De Keukeleire, D., . . . Aerts, G. (2015). Comparison of the Analytical Profiles of Volatiles in Single-Hopped Worts and Beers as a Function of the Hop Variety. BrewingScience, 68, 8-28.

- Rettberg, N., Thorner, S., Labus, A., & Garbe, L. (2014). Aroma Active Monocarboxylic Acids – Origin and Analytical Characterization in Fresh and Aged Hops. BrewingScience, 67, 33-47.

-610x915.jpg)

Are those small filters between the brewbucket and the keg? For keeping hop debris from clogging the poppets?

Yup, exactly!

Hey Scott,

Thanks for the articles. Where can one get those little hop blocker filters?

Thanks

Jon

Here’s a source on Amazon. I’ll say though, I’ve had some issues with them getting clogged if you aren’t able to cold crash or have a way to transfer without pulling in a lot of the hops in your source keg/tank.

Thanks for the thorough (and thoroughly interesting) write-up! Quick question from a hobby brewer. Am I correct in summarizing that cool-fermentation (in the lager range) may have benefits over warm-fermentation when it comes to thiols (3MHA) that affect hop aroma, and that overcoming some aromas and flavors characteristic of common lager yeasts (but not this rediscovered yeast) would allow us to leverage the cool-fermenting characteristics of some lager yeasts in hoppy, aromatic styles traditionally reserved for ale yeasts? If so, how should we be thinking about the lower attenuation and flocculation characteristics of this yeast strain when it comes to an IPL? Are these desirable or undesirable traits in the context of the modern hop-forward recipes that you use?

That sounds like a good summarization. According to one paper anyways, the lower fermentation temperatures did seem to keep thiols around better, of course, this would likely be different depending on the yeast strains used. Strain-to-strain has also been shown to ferment beers with varying concentrations of hop-derived compounds. I tend to like my NEIPAs on the sweeter side (FG ~1.020+), so in some ways I don’t mind the higher FG TUM 35 might produce. But, I would consider mashing lower the next time around (152F or so) to try and bring down the FG and reduce the malt flavor a touch.

Since you compared with 34/70, if you decide to compare with another lager yeast, give the Augustiner strain a try. I like Omega Bayern, but Jasper has it as well. It’s low sulfur and low diacetyl. I start my fermentation as low as 46, but the brulosophy guys have fermented as warm as 66 with clean flavors. It’s worked great on my hoppy pilsners with a blend of American/NZ hops and noble like hops.

I’ll keep it in mind, I haven’t used that strain yet!