I went on a good stretch last year and into this year of using WLP002, a solid English strain, in almost every hop forward beer I made. I’m pretty sure I started using the strain after hearing that Firestone Walker used WLP002 in all their hoppy beers during a podcast. Since then, I have brewed 25 batches with the strain, which seems like enough of a sample size to play with the data a little to see if anything stands out. I decided to focus on the finishing gravity of all the batches and correlate different brewing processes to this figure to explore what factors were influencing the final gravity of WLP002 fermented batches the greatest/least.

I’m not trying to blow anyone’s homebrewing mind with the data (which you’ll see is fairly predictable), I just like taking a step back every once in a while and look at some figures to see if my processes are working in a way I’m intending. There were a couple interesting points I found from this exercise like:

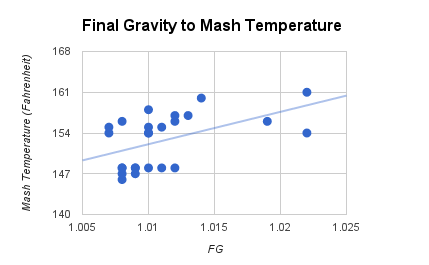

- Mash temperatures at and above 155F started to reliably produced beers with gravities above 1.010, which is how I ended up preferring this strain in hoppy beers. To my palate, I preferred the beers with a little residual sweetness left in the beer which seemed to enhance the mouthfeel a little as well as hide the alcohol warming I got from some of the beers that finished lower.

- The yeast generation and number of days each generation was stored in a mason jar unwashed in the fridge had very little impact on how WLP002 performed. I can feel confident now that simply swirling the yeast cake around with the little beer left in the fermenter after racking into a keg and pouring the mix of beer and yeast into a sanitized mason jar is a good way to keep the generations going. I typically would fill 3 jars with each batch I harvested yeast from and use 1 jar to ferment a future 5 gallon batch (many times without a starter).

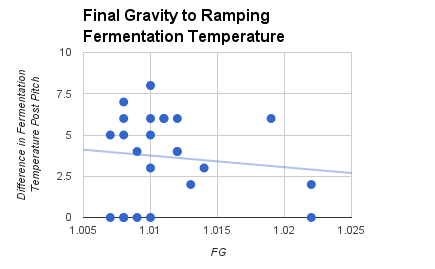

- Although there was a trend line showing higher finishing gravities when the initial fermentation temperature was near its final fermentation temperature, it was very slight. Basically, with enough time WLP002 would ferment out even if the temperature remained the same during fermentation. In fact, I had four batches that finished below 1.010 and never saw a rise in fermentation temperature. I would say that ramping the temperature did seem to speed up the process, but I don’t have any collected numbers to prove that.

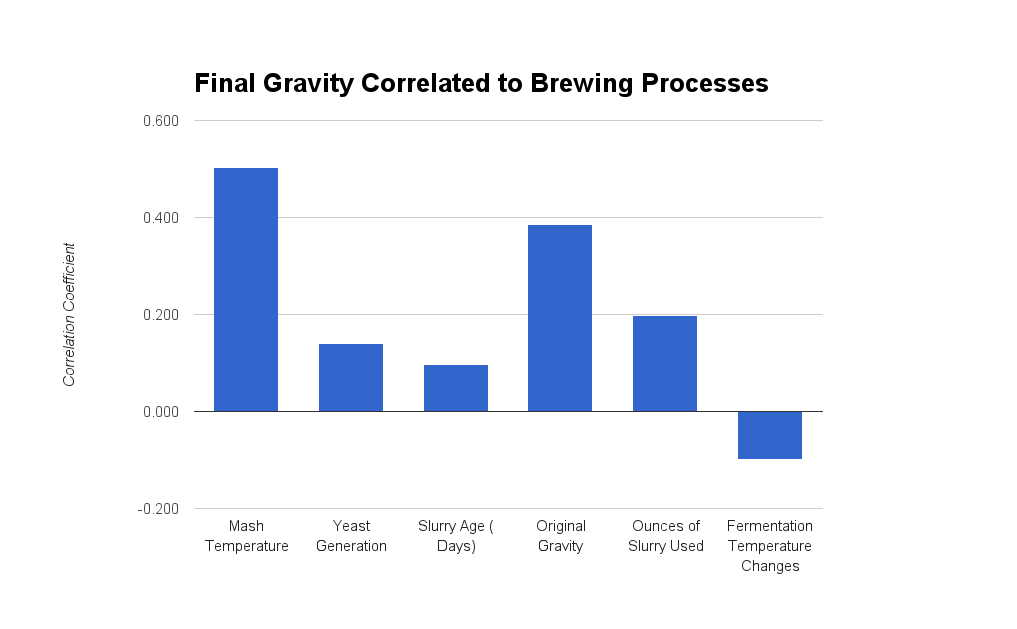

Results – Below is a chart showing a few of the brewing processes I collected for each batch correlated to the finishing gravities. Keep in mind that a correlation coefficient of 0 means there is no relationship and anything at or below .30 would typically be considered a weak relationship and anything at or below .50 is a moderate relationship. Below this chart is a short blurb and chart of each of the brewing processes figures explained.

Results in Order:

- Mash temperature (moderate relationship)

- Original gravity (weak relationship)

- Ounces of slurry used (very weak relationship)

- Yeast generation (very weak relationship)

- Ramping fermentation temperature (very weak relationship)

- Slurry age (days) (very weak relationship)

Mash Temperature – I’m sure this won’t come as a shock to many, but the brewing processes with the highest correlation to the final gravity of each batch fermented with WLP002 was the mash temperature (Correlation Coefficient = 0.504). The chart below shows that this suggests the higher the mash temperature, the higher the finishing gravity tended to be. This wasn’t always the case, as you can see a handful of beers with mash temperatures around 154 that finished rather low. Most interesting in this graph to me is that I started to see more consistent higher final gravities when my mash temperature was at or above 155F.

Mash Temperature – I’m sure this won’t come as a shock to many, but the brewing processes with the highest correlation to the final gravity of each batch fermented with WLP002 was the mash temperature (Correlation Coefficient = 0.504). The chart below shows that this suggests the higher the mash temperature, the higher the finishing gravity tended to be. This wasn’t always the case, as you can see a handful of beers with mash temperatures around 154 that finished rather low. Most interesting in this graph to me is that I started to see more consistent higher final gravities when my mash temperature was at or above 155F.

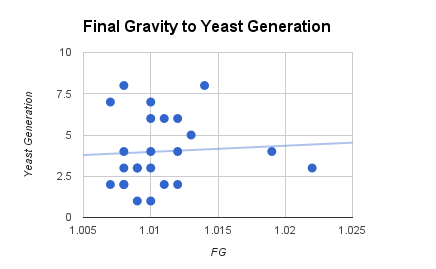

Yeast Generation – The yeast generation didn’t appear to have much of an impact on the final gravity of the batches (Correlation Coefficient = 0.140). This could suggest that harvested yeast if pitched in appropriate amounts seems to chomp up sugars at the same rate as the fresh vials did. In this case, over the 25 batches the average beer was fermented with 3.88 generation of slurry (ranging up to one batch fermented with 8th generation batch).

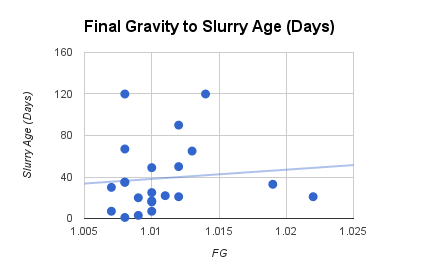

Yeast Age (Days) – The number of days the slurry sat in a mason jar unwashed in my fridge also didn’t have an impact on the final gravity of each batch (Correlation Coefficient = 0.096). As you can see from the chart, even those beers fermented with slurry over 100 days old fermented out just fine. As a side note, for 10 of the batches I didn’t even make a yeast starter prior to being pitched with the average slurry pitched without a starter at 53 days old. If anything, I can say WLP002 is a workhorse, fermenting strongly no matter how I prepped or stored it!

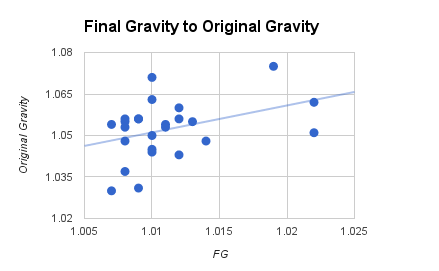

Original Gravity – The original gravity had the second highest correlation to the final gravity of each batch (Correlation Coefficient = 0.386). This isn’t likely a surprise because as the gravity increases and the workload on the yeast increases, the more sugars WLP002 left behind. The chart below shows that in my experience it if wasn’t for 3 outlying batches, this correlation number would have came down. Of the 25 batches fermented with WLP002, the average final gravity was 1.011.

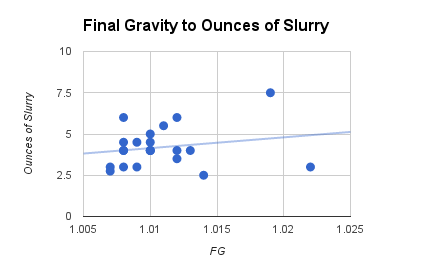

Ounces of Slurry Used – The ounces of slurry pitched into each batch had a minimal correlation (Correlation Coefficient = 0.199). I don’t actually measure each batches slurry amount, I eyeball the amount of slurry sitting in the mason jar that’s compacted below the liquid and use the markings on the mason jar as a gauge. This chart seems to tell me that as long as I’m pitching at and above 2.5 ounces of WLP002 with normal gravity beers, I’m fine (even without a starter). I should say again that I’m not washing the slurry, so the amount of actual yeast is less than the ounces I have indicated because they are mixed with trub from previous batches. I do my best to get very little trub into the fermenters after the boil because I know I will be harvesting the yeast. I typically get the cooled wort going in a good whirlpool then do a 30 min rest to let it settle. I then start emptying the wort from a side pickup discarding the first couple pints or so because this is where I see most of the trub that settled to the bottom coming out of the valve.

Fermentation Temperature Changes – There was a very slight negative correlation of temperatures post yeast pitch and final gravities (Correlation Coefficient = -0.099). I subtracted the end of fermentation temperature of each batch by the yeast pitching temperatures to get a number of degrees difference for each batch. The chart below shows a slight decrease in attenuation when final fermentation temperature was closest to the pitch temperature or the more the fermentation was raised the greater the attenuation, but again this correlation was so low it’s not a convincing number. Given enough time WLP002 fermented out just fine even at consistent temperatures.

-610x915.jpg)

Excellent, concise read. I use similar homebrew practices and am happy to see your success over 25 generations of WLP002, as I am about to switch from WLP090. I feel WLP090 lacks character and WLP002 sounds like an even better choice now that I have seen your highly relevant data.

It really is a solid yeast strain. I did have less than 25 actual generations since I would typically harvest 3 jars of yeast per batch, so I would get 3 new 5 gallon batches out of 1 harvest if that makes sense. Another positive of this yeast is its ability to clear up a beer. It looks like most of the time I would ferment out this strain for 24 hours at 62-63 degrees then ramp it to 66 for about 4-6 days then let it go a little higher to finish out (although this step wasn’t necessary if your going to let it sit at for about 2 weeks).

My mistake, I see it was 25 batches, not generations. 🙂

Nevertheless, good data. I personally have had very good luck with doing 17c (62.6f) for 2-3 days and then 20c until it clears. It’s a practice validated by Zainasheff and Bamforth, and it seems they know a thing or two!

I think you would find the mash temperature correlation to be much higher if a long mash were used. How long did you mash for these tests? Mash time with temp is critical for beta amylase since it acts much slower than alpha. What I have found is that if I want to brew a high gravity beer with a lower FG I overnight mash it at 145F, I have had a 1.085 beer finish at 1.009 using this method. Also 155F isn’t high enough to denature beta which could also have decreased your mash temp correlation number. 158 minimum is required to denature beta from what I’ve read. Also it would have been nice to see pH taken into account as a variable, if you have a pH meter.

I’m not trying to invalidate your results this is good stuff, but if you try this again it would be cool to see those variables taken into account.

This yeast is a beast. I don’t normally make starters, but I opted to for the first time this weekend, putting only 1 Tbsp 2nd gen yeast+trub into 500mL. I only occasionally shook it, and I swear the amount of stuff on the bottom of my mason jar “starter” didn’t even double by the time I pitched. I assumed there were cells in suspension because it was mildly turbid and very mildly fizzy, but even so, I was way below what convention tells me I should pitch (based on looking at the packed cell volume of a white labs tube). Within 18h there was a raft of cells floating on top of my beer and an inch of foam on top of that.

It remains to be seen if the beer will taste good with my piddly little starter, but I’m not worried. I once pitched an expired white labs vial of the stuff directly into a bitter… took maybe four days to get going, but the beer was good in the end.

Great blog by the way. As a scientist I appreciate that you look into the scientific literature for answers.

I’m looking to keep the attenuation low with this yeast in a low ABV hoppy ale. How low can I ferment this yeast and still get solid if a bit lower attenuation? I usually just let her rip at 68F with my probe insulated on the side of my carboy in my fridge and get b/w 68-75% AA usually.

I’d try mashing around 158F to try and encourage low attenuation rather than colder fermentation temperatures.

I’ve been reading your blog lately (learning about it via the Mad Fermentationist blog) and was interested in learning about your yeast washing technique or process. I’ve actually never attempted this before, but now that I can source the Vermont Ale yeast strain (Yeast Bay) I would be grateful if you could provide me with some tips.

Great blog by the way and very insightful to us homebrewers honing our craft!

Hey Marc, I think the easiest way to harvest yeast is to overbuild a starter – http://brulosophy.com/methods/yeast-harvesting/

Hey Scott,

I have been researching which yeast to use for an all English ingredient SMaSH beer and think I will give WLP002 a go. This will be my first time using a liquid yeast and I would like to harvest it after the initial SMaSH beer brew.

When you come to use the slurry in the next brew do you first remove the previous beer that may have settled on top of the yeast, in the mason jar, before adding to the FV?

Thanks

Yup, I’ll decant off the old beer and usually add some of the new wort to the mason jar to help swirl it around so I can pour it all out into the fermenter.

I know this is four years old, but hopefully you’ll see this. What size of mason jars are you using for your 5 gallon batches?

I always used 16 ounces jars.

Thanks, Scott! My next brew is a ESB with the 002, and this was enjoyable to read! Thank you! As a sidenote it was interesting to read about your yeast handling. I wonder for how long you usually dare to keep your slurrys in the fridge before not even wanting to ferment with them using a starter? I like the idea of building a small yeast library in my fridge, but it feels a bit dodgy storing some slurrys for a long time.. Do you have any inputs on that? Thanks again for all your work!

Hey Mikael, this post was a while ago, but I think now I’d probably make a starter after letting it sit for about 2 weeks now. We’ve seen how quickly yeast cells die at the Sapwood and even just a week can be hard on it (especially some of the hazy-forward strains).

Sounds smart. Do you think there is an “upper limit” to how long one could store the slurry before it is out of date? It surely must depend on strain of course.